The Covid-19 virus has shaken the world. But it has also inspired both entrepreneurs and physicians into re-thinking practices. One key area is ventilation and here we discover how a start-up initiative is driving innovation in an overlooked treatment method.

As Covid-19 took a grip on countries globally, its treatment came under the spotlight and it rapidly became clear that many patients arriving in hospitals were in danger of developing Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS).

To alleviate the symptoms, ventilation with oxygenated air is vital with most hospitals using noninvasive ventilation devices devices and ventilators. Such was the spread of the disease shortages of equipment rapidly became apparent.

This led to hi-tech manufacturers such as Mercedes re-inventing themselves to produce continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) face mask device machines in a bid to bridge the supply gap with conventional firms overwhelmed by demand.

But non-invasive ventilation has its shortcomings and sometimes can be harmful, according to Aurika Savickaite, an expert in the field. She has been working to illustrate how another form of ventilation can either replace or complement conventional methods.

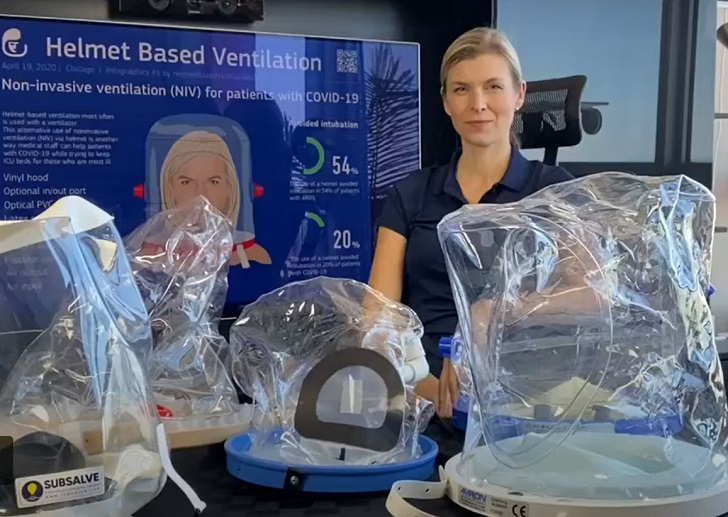

Plastic hood Ms Savickaite is a champion of the non-invasive ventilation helmet, a relatively simple piece of equipment which sees a plastic hood being placed over the patient’s head and attached to existing oxygen and medical air supplies at the bedside.

She argues that prematurely jumping to invasive mechanical ventilation has done more harm than good for patients. Data indicates the mortality rate for Covid-19 patients on an invasive mechanical ventilator is far higher than for those using non-invasive ventilation.

Invasive mechanical ventilation can be extremely painful. As a result, patients need to be sedated but sedation drugs have been in short supply. There may also be more risk to those with already compromised lungs. Ms Savickaite says a non-invasive ventilation helmet solves these problems and prevents the spread of the virus while the patient is still awake and alert. Ultimately it works in about 30% of cases where patients can avoid intubation. That frees up ventilators for more serious cases.

The technology behind helmet-based ventilation is not new. It has been widely used in Italy for more than 20 years where most of the research has taken place. Recent experience at the Monza hospital near Milan, Italy saw 200 patients simultaneously treated via helmet-based ventilation, compared to about 50 intubated patients.

The problem is that while some countries have embraced helmet-based ventilation, others, particularly the United States, have not. Traditional face masks and intubation have always been preferred.

Health system But Covid-19 has put massive pressure on the health system with acute shortages of ventilators so it was in March, as the full impact of the virus was dawning, that Ms Savickaite and entrepreneur husband David Lukauskas were discussing it over the kitchen table. That's when they had the idea to set up the 'Helmet Based Ventilation' initiative and promote the technolgoy as a not-for-profit business.

Ms Savickaite had seen the benefits of helmet-based ventilation first-hand having worked as a patient care manager at the University of Chicago hospital where she was involved in a successful testing program in the intensive care unit during a three-year trial study. She also wrote her final Capstone paper on the subject for her Master of Science in Nursing.

Mr Lukauskas was so convinced of the benefits that the Helmet Based Ventilation website was registered immediately and work began to not only promote the benefits but to seek out new research and development into the technology. So what exactly is a helmet-based ventilator and how does it work?

Design concept Most designs consist of a vinyl hood or helmet placed over the patient’s head with a soft collar neck seal preventing gas from escaping, ensuring a consistent supply. Air output and input tubes are attached along with a port through which water or liquid food can be passed and a viral filter to help minimize the risk of infection among medical staff.

The helmet is connected to the existing mix of gases and effectively the patient breathes normally. Feedback from patients reveals that once they are given the helmet, they do not want to take it off, such is the relief that it offers.

“We find patients tolerate the helmet far better as opposed to a face mask and often they go to sleep quickly as they can finally relax,” said Ms Savickaite.

Intensive care Studies have shown that patients suffering from ARDS do not have to be intubated in more than 50% of cases. Countries such as Italy, Germany and France have also seen patients with higher success rates of recovery and fewer days in intensive care.

One physician familiar with the use of helmets is Maurizio Franco Cereda of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Dr Cereda also practiced in Italy before coming to the United States in 1999. Dr Cereda has started to convince his partners of their benefits with the advent of Covid-19 and they have introduced them throughout the hospital, training staff as they go.

Dr Cereda said: “The goal is to be able to deploy a massive number of helmets as they do in Italy. My aim is to have a system that can be used without any device or machine. I want it to be as simple as possible.”

Helmets can also be used at crucial times. They may not be the appropriate solution but in the minutes or hours a patient is waiting for intubation to be available, they can mean the difference between life and death. “You want to have a bridge for your patients. Put them on the helmet and you buy six, seven hours,” said Dr Cereda. The challenge remains convincing clinicians, already exhausted through treating Covid-19 patients, that helmet-based ventilation can work.

Large scale Ms Savickaite and her small team are in touch with a growing list of US manufacturers capable of producing helmets on a large scale.

Only two companies: Sea-Long Medical Systems and Amron International were already making helmets. At Sea-Long, a team from Oregon led by Frank Selker and his brother John Selker contacted the business and raised US$50,000 of private funding to cover ramping up production. A further US$1m has now been secured for 6,000 helmets and to fund production of up to 5,000 a week as well as further research and development.

Another contributor has been Richard Branson who contacted Sea-Long owner Chris Austin at the beginning of the project and, drawing on his experience in space technology, is providing backing through Virgin Galactic and The Spaceship Company which have also teamed up with experts from the NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center and the City of Lancaster to assemble a Covid-19 task force.

The team have designed and built several prototype patient oxygen hoods which are being tested for comfort, ease of use and functionality while also working with Sea-Long to increase production by financing more machines and sending manufacturing experts to help. David Voracek, lead NASA engineer for the Task Force, said: “We’ve looked across our center’s expertise in innovation, engineering, design, and fabrication of unique systems, to bring NASA knowledge and people together to collaborate on solving the needs and challenges brought about by the Covid-19 situation.” State hospitals Another US company, diving consultancy Lombardi Undersea, has also drawn on its expertise to manufacture helmet-based ventilation units. Owner Michael Lombardi said orders are already being taken with 1,000 units going to the Rhode Island Emergency Management Agency for use in state hospitals.

He also sees the helmets being used in alternative locations such as conference centers which have been repurposed as hospitals as they are easily connected to mobile oxygen tanks in the field. Mr Lombardi believes up to 1,000 units a day can be produced thanks to their simplicity. Development is an ongoing process with physicians making recommendations as the equipment is put into practice, for example by introducing a larger access port that could be used for oral medications.| One of the biggest hurdles is that only a few designs have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) although Sea-Long and Amron International have succeeded.

Ms Savickaite said: “It’s great that so many companies are getting involved with investors supporting them. But I want to make sure they are listening to the customer - the doctor, respiratory therapist, nurse, the patient.

“The key to adoption is convincing clinicians and medical staff that this equipment will not only help them as well as patients, it is also easy to use, saving time and money.”

The technology is relatively cheap compared to a conventional ventilator. Prices for the helmet-based ventilator range from a basic US$125 to US$250 with the full connection kit. Helmets that have been approved are being shipped to Spain, Australia, Ukraine, Lithuania and Estonia and the list is growing.

Smartphone application A smartphone application has now been developed featuring software for the helmet while a Facebook group has been set up to develop a helmet with the aim of publishing instructions online so anyone can build one in an emergency situation.

Ms Savickaite added: “I want to make sure these physicians are using the software. Adjustments to the design will be based on feedback.”

Funding remains a major challenge for Helmet Based Ventilation itself but Ms Savickaite is keen to highlight the positive aspects of running such a small initiative. “If I was working for a big organisation this would not happen so fast. Things are happening on a daily, sometimes hourly basis so it’s stressful. But the results are amazing,” she said.

In just a few months Helmet Based Ventilation has made huge inroads into developing this technology. It is clear that major results could soon start to happen with production increasing due to demand and investment.

Flu season It could be argued that as far as Covid-19 is concerned, it is too late for a developing project such as this. But Ms Savickaite believes that after this period of global infection, it will return in the Fall with major concerns around the next flu season.

“I was initially more focused on the US but now it is becoming more of a global mission because the southern hemisphere will have a flu season very soon and South American countries already have high numbers of Covid-19 patients, she said.

“I hope that in six months we have a helmet that can be used for anyone in respiratory distress, not just a Covid-19 patient, which will protect clinicians from any virus or bacteria. Hopefully clinicians will learn and see the benefits we saw in Italy and at the University of Chicago.”