Water is vital; therefore, waste water has to be cleaned as efficiently as possible. Ceramic membranes make this possible. Researchers from the Fraunhofer Institute for Ceramic Technologies and Systems IKTS in Hermsdorf, Germany were able to significantly reduce the separation limits of these membranes and to reliably filter off dissolved organic molecules with a molar mass of only 200 Dalton.

Anyone who has dragged himself along a sunny coastal path at the height of summer with too little water in his/her bag knows all too well: without water, we cannot make it too long. Water is one of the foundations of life. In industry water is a must, as well: in many production processes, it serves as a solvent, detergent, to cool or to transfer heat. As more and more water is consumed, waste water has to be treated and reused. Ceramic membranes offer a good way to do this: since they are separated mechanically, similar to a coffee filter, they are particularly energy-efficient. However, this method previously came to an end when a molecular size of 450 Daltons was reached; smaller molecules could not be separated with ceramic membranes. According to experts, it was even considered impossible to go below this limit.

Researchers from the Fraunhofer Institute for Ceramic Technologies and Systems IKTS, Hermsdorf, Germany, have now developed ceramic membranes capable of separating out smaller molecules than ever before, enabling the more efficient purification of wastewater.

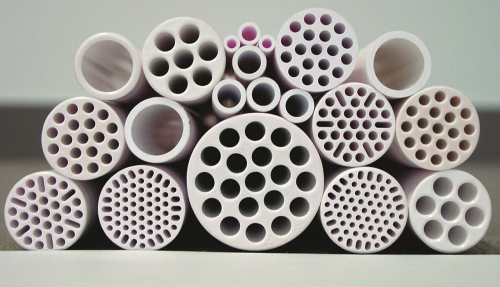

"With our ceramic membranes, we achieve, for the first time, a molecular separation limit of 200 Daltons,” says Voigt, Deputy Institute Director of the IKTS and Site Manager in Hermsdorf. Several obstacles had to be overcome to achieve this result. The first involved the production of the membrane itself. To separate such small molecules reliably, a membrane was needed with pores smaller than the molecules to be separated. The Fraunhofer team has developed a nanofiltration membrane with pores of <1 nanometre. If a liquid is filtered through these pores only water will pass through, leaving behind much of the dissolved molecules and some salts. The membrane can even filter out substances like antibiotics and hormones which are still present in drinking water.

In addition, all of the pores had to be as similar in size as possible, since a single larger opening is sufficient to allow molecules through. "We achieved these results by refining sol-gel technology," reports Richter, Head of Department at the IKTS.

The second hurdle was to make such membrane layers defect-free over larger surfaces. "Whereas only a few square centimeters of surface are usually coated, we equipped a pilot system with a membrane area of 234 square meters, which means that our membrane is several magnitudes larger," explains Puhlfuerss, scientist at the IKTS.

Pilot plant

The ceramic membrane is robust and can withstand heat and chemicals, making it suitable for wastewater processing in oil production. A pilot plant commissioned by Shell in Alberta, Canada, and built by Andreas Junghans–Anlagenbau und Edelstahlbearbeitung GmbH & Co. KG of Frankenberg, Germany, has been successfully purifying wastewater since 2016, which is used for the extraction of oil from oil sand. The researchers are currently planning an initial production facility with a membrane area of more than 5000 m2. Any kind of water can be purified, including surface water, and water from wells or rivers. Heavy metals and dissolved organic substances from agricultural applications can be also removed, for example, herbicides which might have been carried to the surface water. For the development of the ceramic nanofiltration membrane, researchers Voigt, Richter and Puhlfuerss have received this year’s Joseph-von-Fraunhofer award.

www.ikts.fraunhofer.de/en.html